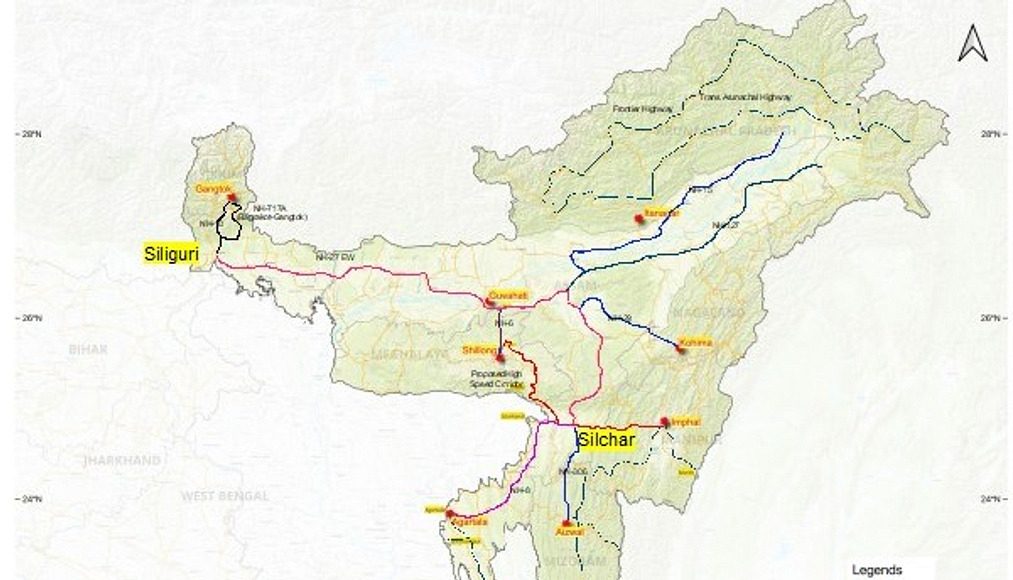

The Siliguri Corridor, often dubbed India’s “Chicken Neck,” is a strategically critical and narrow stretch of land—measuring just 20–25 kilometers wide at its narrowest—that connects the rest of India to its eight northeastern states: Arunachal Pradesh, Assam, Meghalaya, Mizoram, Manipur, Nagaland, Tripura, and Sikkim. Sandwiched between Nepal, Bhutan, and Bangladesh, this corridor acts as a geopolitical linchpin for India’s sovereignty and internal connectivity. In recent years, with mounting border tensions and China’s deepening influence in the region, this vital corridor has become the centerpiece of India’s security calculus and Beijing’s strategic aspirations. For China, the ability to threaten or disrupt the Siliguri Corridor would not only undermine India’s military and logistical cohesion but also offer a potential leverage point in any conflict scenario.

Also Read: China Aids Revival of WWII-Era Bangladeshi Airbase Near Siliguri

Historical Background

The origin of the Siliguri Corridor’s vulnerability dates back to the 1947 Partition of British India. The creation of East Pakistan (now Bangladesh) carved away most of Bengal’s eastern territories, leaving a thin tract of land connecting mainland India to its eastern frontier. The 1971 Indo-Pak War and the subsequent creation of Bangladesh eased some connectivity issues but introduced a new set of challenges as China began cultivating stronger ties with Dhaka. Over the decades, this corridor has remained a pressure point, with India investing heavily in military installations, border roads, and civilian infrastructure to prevent geopolitical isolation of the northeast. Yet, its geographic slenderness ensures that its strategic fragility remains unresolved.

Strategic Importance of the Siliguri Corridor

Geographically, the Siliguri Corridor is India’s umbilical cord to its northeast. It facilitates the movement of goods, military hardware, civilian populations, and energy supplies across the region. All major railway lines, oil and gas pipelines, and power transmission routes converge here, making it the most critical logistics artery for the northeast. What elevates its strategic gravity is its location—flanked by three countries. To the west lies Nepal, to the north is Bhutan, and to the south is Bangladesh.

Any military disruption or blockade here could sever India’s northeastern states from the mainland, creating a logistical nightmare and an existential crisis in terms of territorial integrity. This makes it a classic “chokepoint”—a geographical vulnerability that, if exploited by an adversary, could trigger a national crisis.

China’s Strategic Calculations

From Beijing’s vantage point, the Siliguri Corridor represents a golden opportunity for coercive leverage over India. China’s Western Theatre Command maintains a strong presence in Tibet, equipped with high-altitude acclimatized troops, advanced artillery systems, and long-range missiles. A rapid maneuver through the Chumbi Valley (near the tri-junction of India, Bhutan, and China) could, in theory, bring Chinese forces within striking distance of the corridor. The 2017 Doklam standoff was a direct result of such an attempt—China’s road-building near the Doklam plateau would have allowed it to dominate the corridor through elevated surveillance and firepower. More recently, China’s infrastructure upgrades near the Line of Actual Control (LAC) and its covert interest in Bangladesh’s Lalmonirhat airbase—just 20 kilometers from the corridor—underscore a clear intention to gradually encircle and pressure the corridor from multiple angles. China’s broader strategy appears to be based on exploiting the corridor’s fragility to coerce India diplomatically or gain the upper hand in a limited conflict.

The strategic targeting of the Siliguri Corridor aligns with China’s evolving military doctrines. Under the “Active Defense” principle, the PLA is trained to strike first if an adversary is perceived to be preparing for aggression. Chokepoints like Siliguri, which can paralyze a nation’s logistics and command networks, are considered high-value targets. Furthermore, China’s “Systems Destruction Warfare” model advocates neutralizing an enemy’s decision-making and logistic backbone, rather than simply winning territory. The corridor’s cramped geography, congested infrastructure, and command-dependent transportation networks make it the perfect example of a system vulnerability. Disabling or threatening this node could deliver asymmetric advantages to China without a full-scale war.

Beijing’s strategic approach to India involves both maritime and land-based encirclement. The “String of Pearls” strategy—comprising ports in Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Myanmar, and the Maldives—is complemented by the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) that stretches across South and Southeast Asia. The China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) and the proposed BCIM (Bangladesh-China-India-Myanmar) corridor are elements of this design. Siliguri sits at the intersection of this geoeconomic thrust and military ambition. Investments in roads, bridges, and airstrips in Nepal and Bangladesh aren’t merely economic—they serve as dual-use platforms for military logistics and surveillance, inching Beijing closer to India’s jugular.

India’s Vulnerabilities and Response

India’s greatest liability is the corridor’s geographic and demographic fragility. With over 1.5 million people concentrated in and around Siliguri, the region is densely populated and economically congested. The corridor is narrow enough that a precision strike, a rail disruption, or an airborne landing could cut off the northeast for days—if not weeks. Despite some military modernization, the region still suffers from underdeveloped roads, limited redundancy in logistics pathways, and civilian infrastructure not designed to withstand war-like scenarios. Moreover, India’s northeast continues to be riddled with insurgencies, ethnic fault lines, and political grievances. These internal fissures could be exploited by foreign adversaries or proxy actors to cause unrest, complicating India’s response during a crisis.

India has begun addressing these vulnerabilities through a multi-pronged approach. On the infrastructure front, it is fast-tracking projects like the Shillong-Silchar Expressway, the Sevoke-Rangpo railway line, and the Kaladan Multi-Modal Transit Project to create alternate connectivity routes through Myanmar. Militarily, India has enhanced its posture with the deployment of the Trishakti Corps, multiple divisions of the Indian Army’s Mountain Strike Corps, and two squadrons of Rafale fighter jets at Hasimara Air Base, just 75 km from the corridor. Surveillance systems, including UAVs and advanced radars, have been installed along key axes. Diplomatically, India has intensified engagements with Bhutan and Bangladesh to counterbalance Chinese influence and maintain favorable border cooperation. Combined arms exercises involving air force, army, and intelligence units are now routine in the corridor’s vicinity.

The Bhutan Factor

Bhutan is a critical piece in the corridor’s defense puzzle. The 2017 Doklam crisis stemmed from China’s road construction in Bhutanese territory—territory which overlooks the Siliguri Corridor. Bhutan’s geographical position acts as a buffer between India and Tibet. India’s defense cooperation with Bhutan, which includes military training and joint border monitoring, ensures that Chinese forces are kept at arm’s length from the tri-junction. However, China’s persistent attempts to negotiate territorial concessions in Bhutan, including its proposal for a “package deal,” suggest a long-term strategy to gain physical and political access to Bhutanese plateaus that overlook Indian territory. Maintaining Bhutan’s alignment with Indian security interests is therefore non-negotiable for New Delhi.

Global and Regional Implications

The strategic contest over the Siliguri Corridor is not just a bilateral issue between India and China—it has far-reaching regional consequences. A Chinese move against the corridor could drag in allies and provoke global attention, particularly from the United States, Japan, and Australia, all of whom are part of the Quad and have interests in maintaining a stable Indo-Pacific. Bangladesh’s increasing alignment with China through infrastructure and defense ties, including potential dual-use facilities, could create a pincer scenario for India. In a larger war, the corridor could serve as the first domino, triggering wider regional instability and global economic disruptions, especially in the Bay of Bengal and eastern Himalayas.

Local Dynamics and Demographics

Siliguri is not just a geopolitical asset—it is a living, breathing urban center. Its demographic composition includes Bengalis, Gorkhas, Biharis, and tribal communities, each with distinct identities and histories. Ethnic grievances, if manipulated, could erupt into unrest, providing cover for anti-national activities or external interference. The city’s infrastructure is overstretched; population growth and unregulated urbanization have choked transport arteries. This congestion is not just an economic problem—it becomes a strategic liability in emergencies, as it impedes rapid mobilization and evacuation efforts.

Technological and Cyber Vulnerabilities

The modern battlefield is not limited to guns and boots—it includes bytes and bandwidth. Chinese reconnaissance satellites have revisit times as low as four hours, enabling near-real-time surveillance of troop movements through Siliguri. Fiber-optic cables running through Nepal and Bangladesh, built with Chinese collaboration, raise fears of communication intercepts. PLA-linked cyber units routinely probe India’s transportation systems, targeting command networks and logistics chains. In a hybrid war scenario, disabling digital infrastructure could be as effective as a physical blockade of the corridor, leaving Indian forces paralyzed during the crucial opening hours of conflict.

Scenarios and War Gaming

Indian defense planners have run multiple simulations imagining a “Siliguri Blackout” scenario. Exercises like “Him Vijay” have tested the response capabilities of the Eastern Command under conditions where the corridor is cut off. Alternate air supply routes via Assam’s Advanced Landing Grounds (like Walong and Pasighat), or diversion through friendly Bangladeshi territory, are being explored. However, in a real war, such coordination would need to be swift, secure, and politically viable. Hybrid threats, including sabotage of rail lines or insurgent-backed blockades, are also modeled into India’s war gaming playbooks, underscoring the corridor’s multi-dimensional vulnerability.

Comparative Case Studies

Siliguri’s strategic fragility mirrors other chokepoints in world history. The Strait of Hormuz, vital for global oil shipments, has long been vulnerable to Iranian disruptions. The Fulda Gap during the Cold War was the expected route of Soviet tanks into West Germany, prompting NATO’s forward deployment strategy. Like these examples, Siliguri demands layered defense, redundancy in connectivity, and robust political foresight to avoid becoming the flashpoint of a larger geopolitical conflagration.

Way Forward

In the short term, India must bolster its digital and physical surveillance using AI-powered monitoring systems across key nodes like National Highway 10 and the Sevoke-Rangpo rail corridor. Frequent multi-agency drills involving Bhutanese and Bangladeshi counterparts can enhance response coordination. Over the long term, strategic diversification of access to the northeast is essential. Projects like the Kaladan Multi-Modal Transit route through Myanmar and the Chabahar Port linkage via Iran should be fast-tracked. India must also push harder for Quad-supported infrastructure investments to compete with China’s BRI and reinforce regional resilience.

Conclusion

Lt. Gen. (Retd.) Prakash Menon had said, “Siliguri’s defense hinges not just on troop presence but on pre-emptive diplomacy with Bhutan and Myanmar.”

Siliguri is not just a corridor—it is India’s jugular vein to the Northeast. With China’s encirclement tactics and dual-use infrastructure creeping ever closer, a crisis could emerge not from a full-scale war, but from hybrid pressure points: misinformation, insurgency, cyberattacks, or diplomatic isolation. India’s answer lies in a combined response—military preparedness, technological resilience, diplomatic foresight, and civilian infrastructure development.